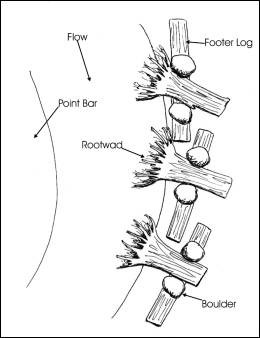

A rootwad is the lower trunk and root fan of a large tree.� Individual rootwads are placed in series and utilized to protect stream banks along meander bends.� A revetment can consist of just one or two rootwads or up to 20 or more on larger streams and rivers.

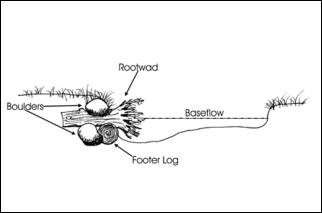

Rootwads are constructed by grading the streambank back and establishing a desired meander radius. A trench is excavated parallel with the streambank along the radius. �Starting at the downstream end of the meander, a footer log (18-24" diameter, 8-10' long) is placed in this trench.� A second trench is cut perpendicular to the first back into the streambank angling downstream.� The rootwad is placed in this trench so the trunk side of the root fan rests against the footer log and the bottom of the root fan faces into the flow of water.� Large boulders are then placed on the top and sides of the footer and rootwad to hold them in place.� Moving upstream, the next footer log is placed in the trench with its downstream end extending behind the first footer log and the next root wad is put in place.� This process continues until all rootwads have been installed.� Some installation methods utilize a cut-off log on top of each rootwad to hold it in place, rather than boulders.

Once the rootwad revetment is in place the area between and behind the rootwads is backfilled with rock/fill.� The top of the stream bank is graded to transition into the rootwads and this area and the area between the rootwads is stabilized with vegetation.

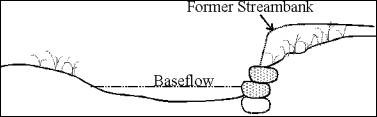

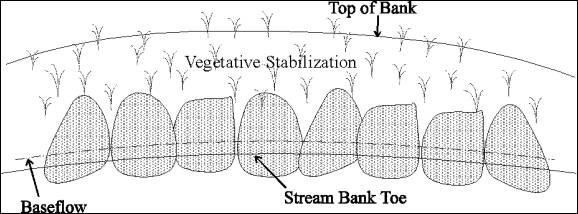

Rootwad revetments have the potential to greatly enhance instream habitat.� Rootwad revetments promote the formation of pool habitat along the outside of meander bends and the root fan portion of the rootwads provides overhead cover for the pools (Figures 1 and 2).�

Figure 1: Profile of Rootwad Revetment

Figure 2: Plan View of Rootwad Revetment

Imbricated rip-rap consists of large two to three foot-long boulders arranged like building blocks to stabilize the entire streambank.� This practice requires boulders that are generally flat or rectangular in shape to allow them to be stacked with structural integrity.��

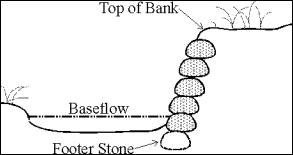

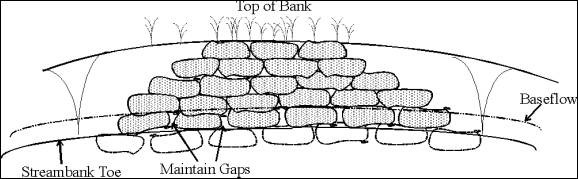

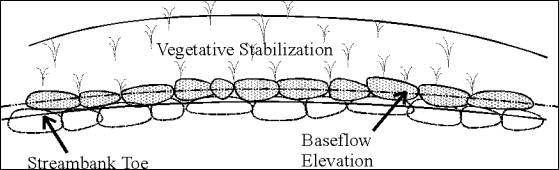

Imbricated rip-rap is installed similar to a boulder revetment, but rises to completely protect the stream bank.� The first step in construction is to grade the stream bank to the desired slope.� This slope is generally near vertical, as one of the main reasons for using imbricated rip-rap is the lack of space necessary to grade the streambank to a stable angle.� Imbricated rip-rap is one of the few practices that can be installed on almost vertical streambanks, where most other measures would fail. After grading the slope, a trench is cut along the toe of the bank for installation of the footer stones. Before placing footer stones in the trench, a layer of geotextile material is secured from the top of the streambank down into the footer trench.� The individual footer stones are then placed on top of the filter cloth in the trench.� Once a layer of footer stone is in place, the wall can be built with each stone overlapping the one underneath it by half. The stones that are placed above the footer stones but below baseflow level should be set so as to create void space between the adjacent stones. The process is continued until the desired wall height is reached.� The top of the bank is then transitioned into the imbricated rip-rap wall and stabilized (Figures 3 and 4).

Imbricated rip-rap has only a modest potential to enhance stream habitat.� The void spaces between the rocks that lie below the waterline provide hiding and cover areas for fish.

Figure 4: Section View of Imbricated Rip-Rap

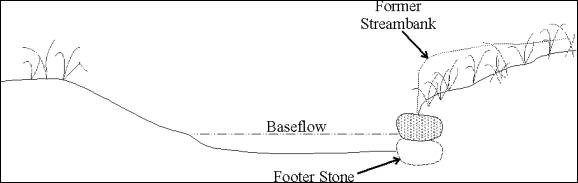

Figure 5: Section View of Single Boulder Revetment

Boulder Revetment (single, double layer, large boulder, placed rock)

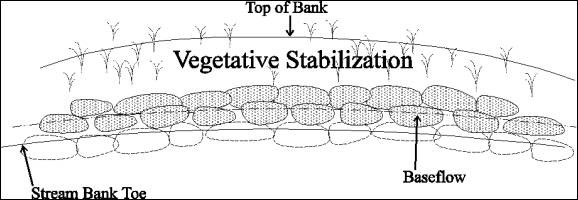

Along streams, the most erosion prone area is the toe of the streambank.� Generally, the lowest third of the stream bank experiences the highest erosive forces.� Failure at the toe of the streambank can result in failure of the entire bank and lead to large influxes of sediment to the stream. Boulder revetments serve to protect the most vulnerable portion of the stream bank. Boulder revetments are often combined with bank stabilization for the streambank area above the revetment.� On smaller streams, where bank heights may not exceed a few feet, boulder revetments (single, double, and large) can provide both lower and upper bank protection.

A boulder revetment consists of a series of boulders placed along a streambank to prevent erosion of the toe of the bank and in some cases to protect the entire bank.� A single boulder revetment is created by first excavating a trench below the invert of the stream along the toe of the stream bank.� In this trench, a series of generally large flat or rectangular boulders is placed as a foundation for the revetment stones.� Once the foundation stones have been installed, the revetment stones are placed on top the foundation.� If protection is needed higher on the bank, a second set of stone may be placed on top of the first (e.g., double stone revetment) (Figures 5 - 8).

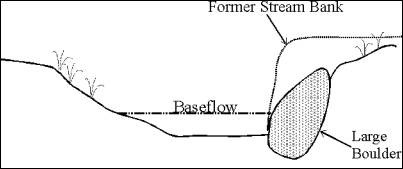

Often, a single row of large boulders three to four feet tall are used to create a revetment.� If large boulders are used, it is important that they be entrenched below the stream invert to prevent scour from dislodging them. Otherwise, the construction of a large boulder revetment is similar to single and double boulder revetments (Figures 9 and 10).

Boulder revetments have only a modest potential to enhance stream habitat.� As most boulder revetments are made of variously shaped boulders there is less potential to create void space below the waterline than with, for example, imbricated rip-rap.� Boulder revetments have a more indirect role in habitat enhancement by reducing streambank erosion and subsequent sediment influx to the stream.

Figure 6: Profile View of Single Boulder Revetment

Figure 7: Section View of Double Boulder Revetment

Figure 8: Profile View of Double Boulder Revetment

Figure 9: Section View of Large Boulder Revetment

Figure 10: Profile View of Large Boulder Revetment

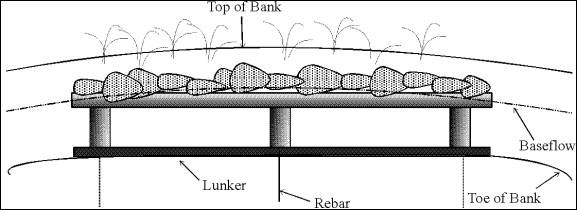

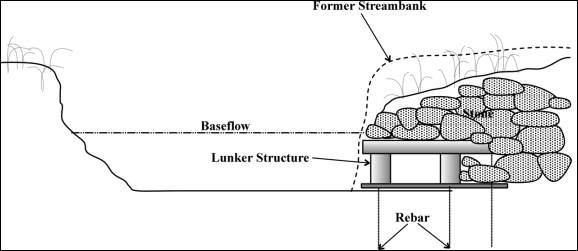

Lunkers are crib-like, wooden structures installed along the toe of a stream bank to create overhead bank cover and resting areas for fish.� These structures were originally developed in Wisconsin for trout stream habitat improvement projects, but have been found to work well in Midwestern streams as bank protection devices.� A lunker consists of two planks with wooden spacers nailed between them.� Additional planks are nailed across the spacers perpendicular and a crib like structure is formed.�

The structure is installed by first grading the streambank back and creating a trench along the new bank line.� This trench must be wide and deep enough so that the lunkers lay flat and are completely covered by water.� The lunkers are secured to the stream bottom with rebar. Once in place, rock is placed on top of and behind the lunkers and the streambank is graded down to meet the front edge of the lunker. The upper bank is then stabilized using bank stabilization techniques (Figures 11 and 12).

Lunkers were originally developed as habitat enhancement structures.� As such, they have a significant potential to improve stream habitat in the form of undercut banks and overhead cover.

Figure 11: Section View of Lunker Structure

Figure 12: Profile View of Lunker Structure

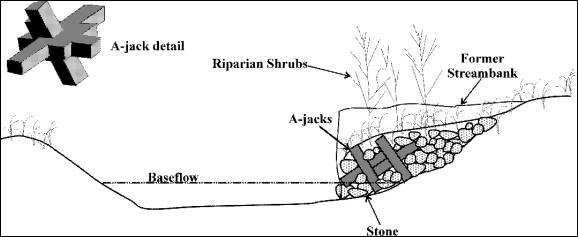

A-jacks are three two-foot long cement stakes joined at the middle (six one-foot legs).� They are a commercially made concrete product, originally made much larger (10-foot legs) to serve as breakwaters along shore fronts. They have been in use in the Midwest for several years. They serve to add structural stability to the lower stream bank.�

A-jacks are manufactured in two pieces each weighing 45 lbs and are assembled onsite. The first step in the installation is to excavate a shallow trench along the toe of the stream bank.� The A-jacks are assembled and placed in a row(s) along the trench so that each a-jack is interconnected with its neighbor.� Rock, geotextile material or coir fiber is placed in the voids between the legs, and the a-jacks are backfilled.� The upper bank is then stabilized using other bank stabilization techniques Figure 13).

A-jacks have a modest potential to improve stream habitat, similar to that of placed rock or boulder revetments.�

Figure 13:� Profile View and Section View of A-jacks